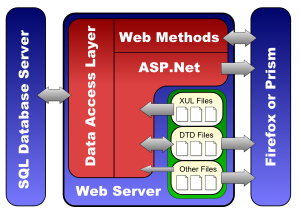

As my previous post described, there are a whole load of different technologies that are jammed together to produce the applications I’m writing at the moment. In order to provide a little more insight into what’s happening – and so that I can talk about aspects of it in more detail in future posts – I’ve produced a diagram to show the main areas of data flow in the application:

Each of the three large blue boxes represents a different computer. On the left is the database server – we support SQL Server and Oracle. Ultimately this is the real purpose of the software – to put data into the database, and to get it back out again.

In the middle is the web server. As we’re a Microsoft shop we use IIS with ASP.Net – though I do some of my prototype work on a Linux box with Apache and PHP, as that’s more familiar territory for me. The red bit in this box represents the ASP.Net code. The green bit represents the machine’s hard drive – or at least the bits of it that are of interest to me.

Finally, on the right, is the client machine running Firefox or Prism. In theory our code should work on other Gecko-based browsers, but we primarily test on Firefox, and support Prism for those customers who don’t want to install a “browser”, but are happy to install a “runtime environment”. Due to our decision to use XUL as our interface language, the code won’t run on any non-Gecko browsers.

The aim – other than putting data into the database – is to generate a user interface on the client machine. If we were just producing a simple, static web page that would be easy – put the file on the web server and point your browser at it. However we need to be a bit more sophisticated than that – so there are quite a few steps that take place when the user requests a “page” of our application. Amongst other things the ASP code injects various strings into the XUL page to ensure that the browser requests the right support files – translations, images, CSS and so on. It also generates translation files from language information stored in the database, and injects the appropriate translation file into the page.

Once the page arrives at the browser, the user can interact with it. Most of our XUL interface consists of our own special widgets which makes them far more powerful than a normal text entry field or checkbox. Those special widgets talk to the server via ASP “web methods”, called using XMLHttpRequest. The result is that our widgets can get data from the database (or put data into it) without having to reload the page – making the application seem far more like a normal desktop application than a web app. It’s the same trick used by GMail and countless other sites these days – but with the framework that XUL gives us we can easily produce a much richer interface than you get from an HTML-based application.

Comment (1)

Comments are closed.