XBL – a dubious abbreviation for eXtensible Binding Language – is perhaps the most important part of the XUL platform that we use, other than XUL itself.

XBL is a mechanism for encapsulating a XUL UI and javascript code into a composite widget that can be used in an application as though it was any other XUL element. In other words XBL lets us create XUL widgets of our own devising.

This is an invaluable asset because it allows our framework to hide a great deal of complexity inside these XBL widgets, whilst providing a simple interface to our application developers. When one of our developers uses a <tfs_passwordbox /> element in a page, they don’t need to know that, within the XBL, that apparently simple widget is actually constructed of half a dozen XUL elements (buttons, textboxes and images), together with a few hundred lines of code. They don’t need to know that it automatically connects to the database to retrieve the site’s password rules governing length and complexity. They don’t need to know about the other connection to the database it makes in order to get a list of words that aren’t allowed to be used in a password (typically the username and company name, at least).

All the developer has to do is to type <tfs_passwordbox /> into their code, and they get all that complexity for free.

Or how about our “lookup box” element – perhaps the most commonly used element amongst our applications. In its simplest incarnation the developer just has to type <tfs_lookupbox /> to get a widget looking like this:

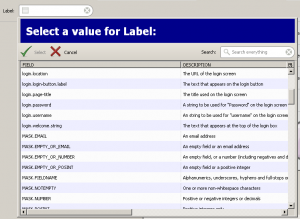

The “lookup box” is so called because it can be used to look-up data in the database. When the user double-clicks on it, or clicks on the button at the left edge of the box, they will be presented with a popup dialogue like this:

The columns are automatically generated, based on the database table that the application is pointing to. The search field lets the user perform a free-text search within all of the data in the popup – or they can use the button at the left of the search field to restrict the search to a particular column. The columns can be sorted, rearranged, hidden and revealed. An entry from the database can be selected by double-clicking on a row, or by highlighting the row then clicking the “select” button.

The developer gets all of this functionality for free, just by using a <tfs_lookupbox /> widget in their page.

Of course not every application – or even every field in a single application – is the same. Sometimes a field has to be read-only, or must force the user to type something in, or force them not to type something, or show a different set of columns than the default, or get the data from a different table than the one the rest of the application uses. Thankfully our XBL-defined widgets can include attributes, just like any other XUL widget, which can then be accessed from within the XBL definition in order to modify the appearance or operation of the widget. So when our developer needs a field to be read-only, they just have to use <tfs_lookupbox readonly=”true” /> to get a widget like this:

There’s a lot more that can be done with XBL – a lot more that is done within our framework in order to make an application that it both powerful for the user, and simple for the developer. And when we have a great idea to improve our widgets (or just when a bug gets fixed), a change to the XBL means that the change automatically applies to every widget in every application, with no need for the developer to go around trying to find and change them individually.

You may have noticed that this post has been a glowing recommendation of XBL, but with a distinct lack of real sample code. That’s quite deliberate – XBL is a big enough subject that any post of mine wouldn’t do it justice. The full details can be found across several pages of the XUL tutorial on Devmo. Suffice to say that XBL is such a powerful and flexible tool that the W3C has started to ratify a new version of it (of course, given the speed at which the W3C usually works, it might become a recommendation by about 2020, and then actually appear in more browsers than Firefox by 2030). Still, I live in hope that one day I will be able to use XBL with HTML content across various browsers – maybe then HTML will finally be powerful enough to displace XUL for our framework.